|

San

Francisco Frequency |

|||

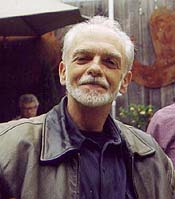

One of the best-known art writers in the U.S., Kenneth Baker began his career at the Boston Phoenix and has been the resident art critic at the San Francisco Chronicle since 1983. He covers a wide range of contemporary and historical art exhibitions, writing on the Max Beckmann retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the "Illuminating the Renaissance" show of manuscripts at the Getty along with art events of more local interest. His is the author of Minimalism: Art of Circumstance (Abbeville, 1989) as well as many catalogue essays. Artist Oriane Stender talked with Baker in San Francisco's Mission District on Aug. 19, 2003. Oriane Stender: Did you start writing about art because of a passion or a mission of some sort? Kenneth Baker: Oh, would that I had a mission. I was an art history major as an undergrad as well as an aspiring draft dodger. While I was waiting to realize that ambition, I wrote a few pieces for the Christian Science Monitor, where I worked as a copy kid. And, to my astonishment, the paper published them, and then wanted more. I thought, well, maybe I can do this. OS: Do you feel there is still such a thing as a regional artistic style or sensibility? KB: First of all, everyone moves around so much now that nobody's going to be regional for very long -- five years is about it. And anyone with art school training is going to see the "international style" as the common tongue of sophisticated art, so they'll be looking to avoid being identified as merely regional. Though the notion of a regional style is still there, I don't think it matters like it did, as a source of motivation for people, or as a source of solidarity. I may be wrong, but I don't see it happening here. Do you? OS: Well. . . recently we've seen a lot of artists, like Barry McGee and Margaret Kilgallen, making these giant "street art" wall murals. KB: Something about that look became bait for ambition. I'm not quite sure what it was; maybe people saw it as a ticket out of here, the fact that these people were able to use this style to project themselves into a larger context of critical awareness. They thought, "Well, maybe I can do the same thing, sort of ride that train out of here." OS: Do you feel that artists have become too commercialized or too focused on success? KB: Oh, certainly not. I see wonderful work being done everywhere, all the time. Some of it's very slight, but that doesn't matter. That only matters if you're interested in ranking, rather than the surprise and experience and cogitation and humor and so on that actually come out of the experience of making stuff and looking at it. So it's that endless opportunity for discovery that keeps me interested. I'm continually surprised by what I see. The rebirth of artist-run galleries in San Francisco is a terrific symptom of reawakening life on the scene. OS: Are there any particular galleries you would cite? KB: Well, Spanganga certainly is one, and Lucky Tackle. Some are very short-lived, and I never get to them before they're gone. But that doesn't matter so much as the fact that the effort is being made again, and the heart for it is there, the hope for it is there. OS: What do you think about the influence of wealthy trustees on the purchasing and exhibition policies of museums? KB: I think it's an inevitability, part of the price of private sponsorship. It's not necessarily a bad thing; a lot of good work, and really expensive work that would be unattainable in any other way, does make its way into museum collections and therefore into the public mind and eye, to an extent that might not be possible in any other fashion. OS: You don't think there's a danger of trustees influencing curatorial decisions? KB: Sure, there's always the danger, and the board has a say in hiring of curators anyway. But we've done pretty well here, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, with Gary Garrels and Madeleine Grynsztejn. She's really a stellar curator. Although she operates so quietly and self-effacingly, and the acquisitions she's made have made no news (except insofar as I've reported them), they've been very smart choices. It's money really well-spent, and much of it not household names, but really important stuff for the collection. The trustees obviously approved her hiring, so they're doing something right. There is actually quite a bit of integrity that comes with that kind of money, along with the sort of power-madness. I know some of these boardmembers and I actually think highly of some of them. Others. . . just like any club, there's going to be some members who are sympathetic, solid people, and others who aren't. OS: Many critics write catalogue essays for exhibitions, and sometimes organize shows as well. Do you do this? And do you feel it impinges on a critic's impartiality? KB: Well, everybody accepts the fact that when writing a catalogue essay you're in an advocacy position. That's just the nature of the task, so you hang up your gloves when you take that on and I have no problem with it. The catalogue essay also gives you a chance to discuss things at length that otherwise you may never have in print. I do write for catalogues, but I don't do it for anybody in this area, anybody that I'm expecting to have to look at critically. But for institutions elsewhere, even for galleries elsewhere, I'll do it. I have an essay in a forthcoming book that Peter Blum is bringing out on David Rabinowitch's early monotypes, which have never been shown or published before. He's somebody whose work I think is widely misunderstood, especially in this country, and in whose work I believe strongly, so I'm glad I had the opportunity to write about it. As far as organizing shows is concerned, there is a rule against that. You can't organize exhibitions and write about them as well. OS: Have you ever made art yourself, or experimented with it? KB: No. I used to try to do some drawing every so often, partly just to get away from words. But also to remind myself of the difficulty of being specific in that way, of actually addressing the specific reality that's out there, and the specific reality of making marks. Writing is one sort of transcription of the observed and drawing is another, so I used to like to do that, and would still like to, except that I have no time these days. OS: But you don't do it with the sense of trying to understand what an artist does so that you can write about it in a different way? KB: No, I don't think that I will ever have the time or energy or resources to participate at that level. Because I think it's a way of life and I can't conduct more than one way of life at a time. OS: What other writers in the field do you find valuable? KB: John Berger is always inspiring. A couple of Arthur Danto's books. I do subscribe to the Nation so I see Danto's work regularly. I can't always get into it, but he's certainly an interesting mind and I know him a little bit and he's been helpful to me. And Dave Hickey. I think Dave Hickey's Air Guitar is really a great book, but I don't find him useful on art per se. I think he's a great writer but I don't find him a critic I can work with. Otherwise, it's pretty much catch-as-catch-can. I don't read art magazines. I don't have time; I've got books to read. There's just too much important reading to do. And I don't find other art writing stimulating. . . . It's poetry that I've found most stimulating lately. And I'm in no way systematic about it, you know, it's wherever I happen to find it. The London Review of Books, for instance, frequently publishes James Lasmin and August Kleinzahler, a San Francisco poet whose work I really admire. Other things just catch my eye. . . . I keep Edward Hirsch's book The Demon and the Angel close at hand because even though I don't like him as a poet, as a reader of poetry he's really good. And Clive James' essays on Philip Larkin are wonderful, not just because of what they say about Larkin, but because the quotes he chooses are so terrific. . . . The way the language actually operates in these lines, the way one thought connects with another, the way the phrases are broken and the way the rhythm plays against the overt meaning and so on. I find it very instructive. OS: I understand that aikido is an important part of your life. Is it like a spiritual retreat? KB: No, no, it's central to my understanding of what I'm doing professionally. I teach a class in aikido at the California College of Arts and I do that because so much of the work that I see is too head-driven, and aikido is about, among other things, bringing the heart forward, both in posture terms and in terms of a source of action, a source of the spirit in which you do things. It's a heartless world, in all sorts of ways, and this kind of practice wins back some ground from that condition within which we all have to exist. And because it's a partner practice throughout, with the partners always changing, it's also a way of experiencing people in a kind of detail that ordinary social existence doesn't permit. I mean you really have intimate contact with people in a way that continues and develops and becomes quite deep. But it's also impersonal, it's asocial, it's nonsexual, it's ritualized and formalized in the sense that most of your attention is to the process. So much of what you experience on the mat seems to be completely cut off from language, but when I'm teaching I try to speak some of the unsayable, try to bring up some of that proprioceptive knowledge into the level of what can be shared. OS: Proprioceptive? KB: Proprioceptive. It means the internal experience of your own body and its position and motion. To me that's very close to the exercise of critical perception. When you look at an object and you try to say something about why it stirs you, why it excites you, something that isn't simply intellectual, something that really is at the level of feeling, then you're trying to connect to language something that is basically nonlinguistic or nontranslatable. So that effort to try and shine the light of language on these dark areas of our experience is very much connected to what I do in critical practice. It's also about the challenge to the ruling values of this culture at the moment, when there seem to be these psychological billboards everywhere saying, "You've got to win at all costs" and "Take no prisoners" and "Yield to no one." It's an alternative path around these hardened goals and priorities that are invisible or unarticulated, and really not what we want if we're right-thinking people -- you know what I mean? ORIANE STENDER is a San Francisco-based artist. |

|||